The present groundwater contour map describes the groundwater situation of the Main Aquifer with violet groundwater isolines and the Panke Valley Aquifer in north-eastern Berlin with blue isolines. The interval between the groundwater isolines is 0.5 m. These show the potentiometric surface area of the unconfined and confined groundwater, respectively (see also Fig. 3). In areas of the Main Aquifer with confined groundwater, the groundwater contours are displayed in broken lines. In areas with no main groundwater aquifer, or with an isolated main groundwater aquifer of low thickness, no groundwater isolines are displayed. Those areas are shown with black dots.

The map is based on the topographical General Map of Berlin, scale of 1 : 50,000, in grid format, and the geological outline for the Berlin state territory, at a scale of 1 : 50,000, which was derived from the geological General Map of Berlin and Surrounding Areas, scale of 1 : 100,000. In addition, the appropriate support points (groundwater measurement points and surface-water levels) as well as the individual waterworks are indicated, with their active wells and water conservation areas.

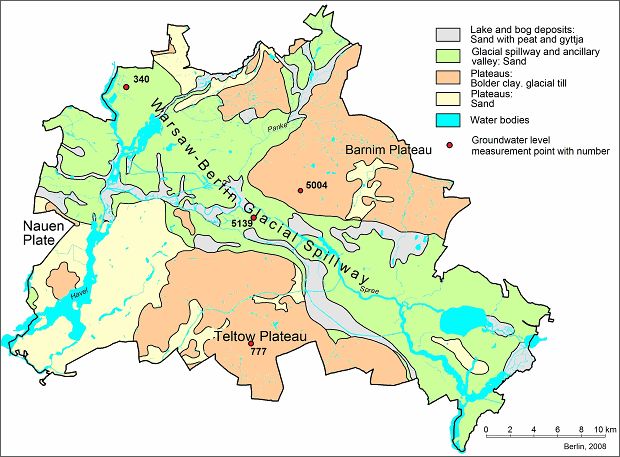

Hydrogeological Situation

On the plateaus, the main aquifer is extensively covered by the glacial till and bolder clay (aquitards) of the ground moraines. Wherever the potentiometric surface of the main aquifer lies within such an aquitard, groundwater conditions are confined. In sandy segments above the till or in islands, near-surface groundwater may be formed, which is also called stratum water (see also Fig. 3). After extreme precipitation, it may rise to the surface. The groundwater levels of these locally highly differentiated areas have not been separately ascertained and portrayed.

In the Panke Valley, on the northern side of the spillway, the Barnim Plateau, a major independent coherent aquifer has developed. It is located above the main aquifer, which is covered by the glacial till of the ground moraine (see also Figs. 7 & 8). On the present map, this aquifer is indicated by separate blue groundwater isolines. A spur of the glacial till toward the Warsaw-Berlin Glacial Spillway creates an interlock of the Panke Valley Aquifer with the Main Aquifer there.

For more information, see the Groundwater Brochure:

www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/_assets/umwelt/wasser-und-geologie/publikationen-und-merkblaetter/grundwasser-broschuere.pdf (only in German)

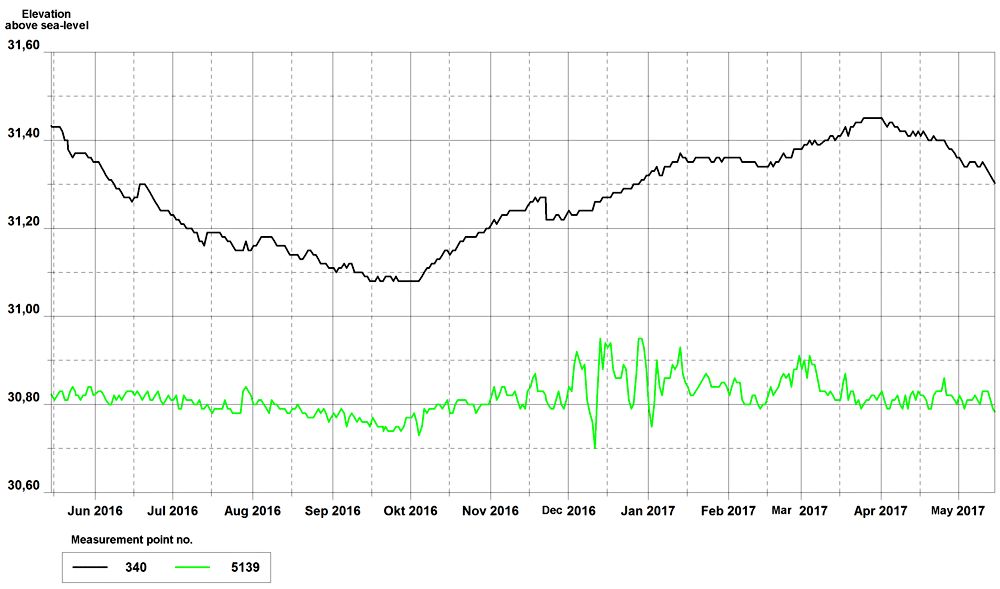

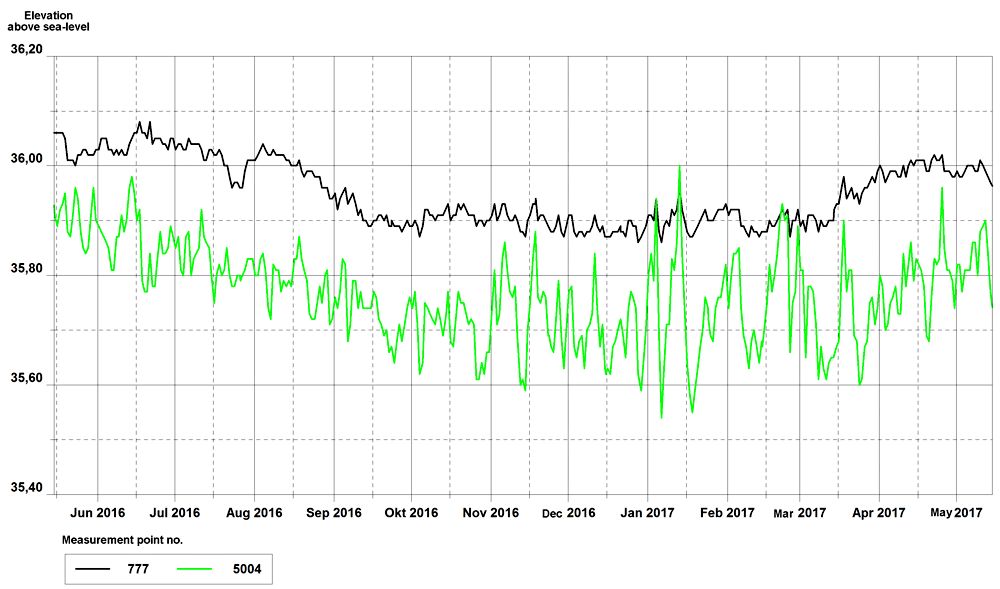

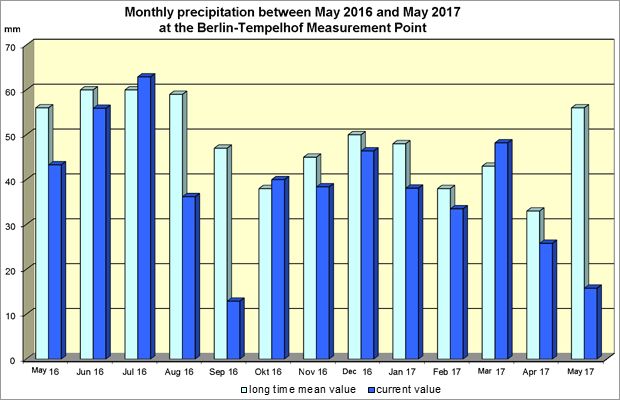

Current Situation in May 2017

As a rule, the groundwater incline in Berlin, and hence, too, the flow direction, is from the Barnim and Teltow Plateaus and the Nauen Plate toward the receiving bodies, the Spree and Havel Rivers. Depression cones have formed around the wells at those waterworks in operation during the measurement period, and have sunk the phreatic surface below the level of the neighbouring surface waters. Thus, in addition to inflowing groundwater from the shore side, the water pumped here also includes groundwater formed by infiltration (bank-filtered water) from these surface waters (see also Fig. 4c).

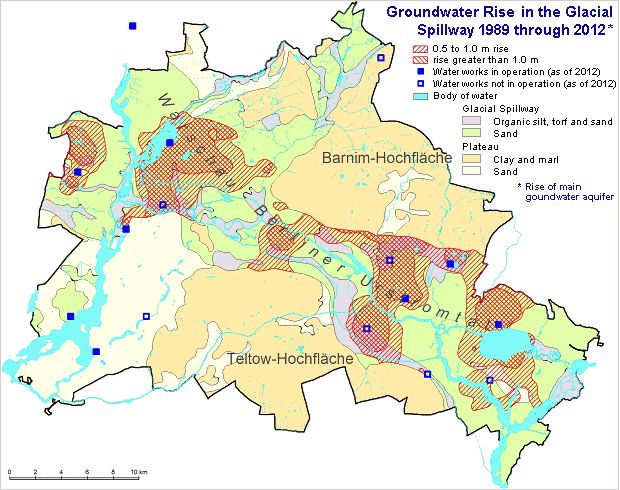

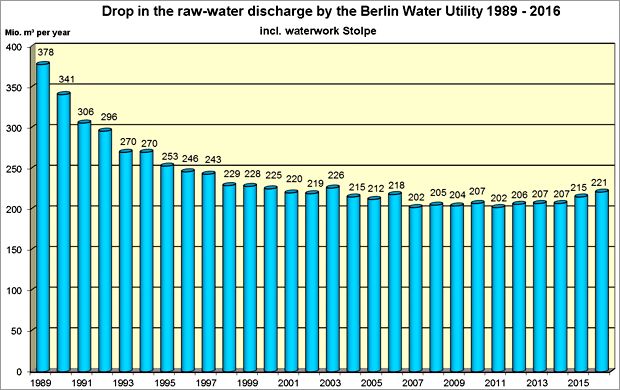

In May 2017, too, the potentiometric surface, which has been lowered in Berlin by drinking-water discharge over the past hundred years, was at a relatively high level compared to 1989 (Limberg et al. 2007: pp. 76 ff.). Areas in the Glacial Spillway in which the groundwater rebounded over this period of time by more than half a meter and by more than one meter, respectively, are shown on the difference map 1989-2012 (Fig. 10).