Berlin’s waterscape was formed during the second, the so-called Brandenburg Stage of the Vistulian Glaciation, which ended about 10,300 years ago. The Berlin glacial spillway is part of the Glogau-Baruth glacial spillway, which extends along the Vistulian end moraines of the Brandenburg Stage. It starts at the mouth of the Prosna, where that river empties into the Warta in western Poland, and proceeds along the Obra to the Oder, along the Oder from Nowa Sól to the Bobr and the Neisse, and then from Forst across to the Spree around Lübben, across to Luckenwalde and Tangermünde, and finally to Brandenburg-on-the-Havel and down the lower Havel to the Elbe.

At the end of Vistulian Glaciation, the waters of the Vistula, Warta and Oder, flowing northward from periglacial areas, were dammed by the inland ice and drained away toward the west, to where the Oder is today, and further toward the Havel and Elbe. Moreover, at all inland-ice advances up to the Ruhr District, there were connections between the Rhine, Weser and Elbe systems which were passable for aquatic organisms (Hantke 1993).

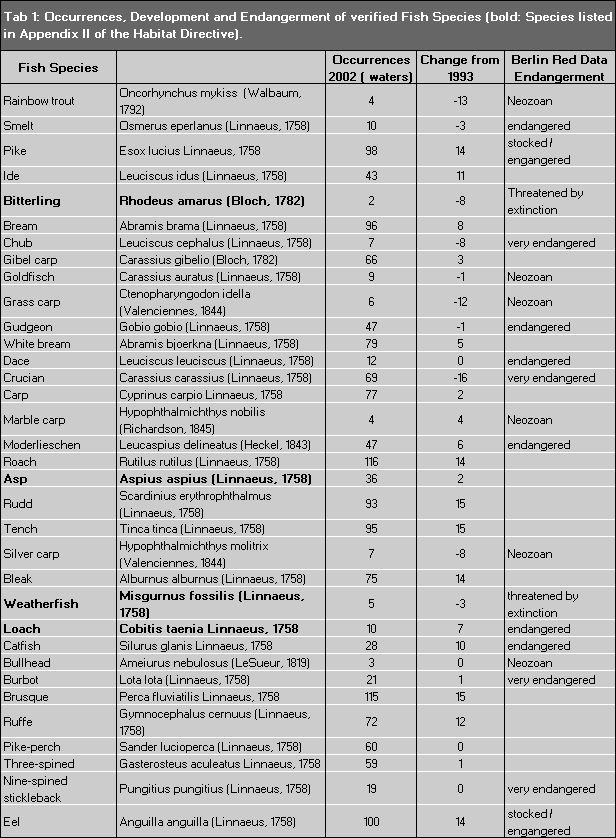

This postglacial waterway network made it possible for three lamprey species and 33 fish species to populate the bodies of water of what is today the state of Berlin (Wolter et al. 2003). These species are considered the original or indigenous fish fauna of Berlin.

Due to their low gradient, the lowland rivers were early the object of hydraulic engineering impairments such as dams, weirs or canal connections between different river watersheds, which reached an initial climax during the Middle Ages. Once, the hydrodynamics of the Spree and the Havel characterized Berlin’s water network; later, these rivers were increasingly dammed and regulated. The construction of dam facilities along river and creek courses began during the early days of the Askanian dynasty, which took possession of the Markgravate of Brandenburg in the 10th century (Driescher 1969). In Berlin, dam construction for the operation of mills can be traced back at least to the 13th century. The first documentary mention of a mill dam is in 1261 at Spandau. In 1285, there was a water-mill in Berlin, and the Berlin Mühlendamm (Uhlemann 1994) is certified for October 28th 1298. However, a 1232 document indicates that a dam facility already existed in Spandau at that time (Natzschka 1971, Driescher 1974).

Many dam facilities are moreover probably considerably older than their first documentary mention would have us suspect. In 1180 for example, Spandau Castle and its castle town were moved about 1.5 km up the Havel, to today’s Old Town Island, due to a disastrous rise in the water level of the Havel caused by a mill dam at the city of Brandenburg, which already existed earlier than 1180 (Müller 1995).

In addition to mill dams, other dam facilities for the regulation of the water level and the promotion of navigation were also built. The straightening of single river sections already began during the 17th century. The lower Havel – for fish, the main colonization pathway into the Berlin waters – was regulated comprehensively for the first time between 1875 and 1881. In the context of the "Melioration of Receiving-Stream and Navigation Conditions on the Lower Havel" of 1907-1913, not only new breakthroughs and cross-section enlargements, but also three additional dam facilities were built at Grütz, Gartz (both 1911) and Bahnitz (1912).

By 1914, the Havel was fully channelized as far as Spandau, with a channel depth of at least 2 m ensured, even at low water levels. This regulation led to a dramatic collapse of the fish populations, and thus almost to the death of the Havel fishing industry. At that time, 1,100 fishermen lost their livelihoods on an 80-km stretch of the Havel, and sued for compensation (Kotzde 1914). It was now no longer possible for migrating fish to overcome the weirs, even at high water levels, and to reach the Berlin area. The dam facilities not only interrupted vitally necessary migration routes, but also destroyed valuable habitat structures in the streams, as well as the flooding areas necessary for many fish species. The flow speed was cut, so that fine-grained material was deposited in the sediment, causing the coarse-grained sediments to be overlain with mud. Oxygen-consuming degradation processes in the stream-beds became predominant. For fish species which prefer a gravelly substratum rich in oxygen, there were no longer suitable spawning grounds and habitats, and no possibility of carrying out compensatory migration, so that e.g. the barbel, a typical river fish which had formerly been the dominant fish species, became extinct in the lower and middle Spree. By the end of the 19th century, waters of the Spree in Berlin changed their character from that of a classic barbel area to that of a bream area (Wolter et al. 2002).

In addition to these permanent impairments caused by waterway melioration, immissions of all kinds had an effect on long-term aquatic conditions. Even before the turn of the century, the pollution of the Spree and the Havel by industrial and municipal wastes and from excrement was so heavy that fish death was common, and fishing was seriously impaired. For instance, due to the poor oxygen supply of the water, it became impossible to transport living fish to Berlin (i.e., today’s central Berlin) in the water from the Lower Havel in so-called drebels, i.e. boats with open, flow-through fish boxes; they died on the way. The establishment of city sewage farms provided only limited remedy of the water quality situation. Pollution was particularly dramatic in the Spree, which received so much sewage immission on its way through Berlin that all animal life on the river bed was eliminated below the Charlottenburg sluice (Lehmann 1925). These anthropogenic effects caused additional impoverishment of the Berlin fish fauna. In addition to the migrating lampreys and fish species and the barbel, other species which required fast-flowing and oxygen-rich water, such as the pond lamprey and loach, died out in Berlin waters. The eutrophication caused or promoted by nutrient immissions favored euryecoid (environmentally tolerant) fish species, whose increase often concealed the decline of more demanding species.

These effects of the historical impairment of the bodies of water in Berlin on the fish fauna were summarizing in 1993 in the first complete Berlin edition of the Environmental Atlas (edition 1993), and in supplementary booklets (Vilcinskas & Wolter 1993, 1994).

The purpose of this edition, in addition to updating and completing the verified results, is to present the development of the fish association and its changes over the past ten years.