Urban climate and health – a challenge for the design of urban living spaces

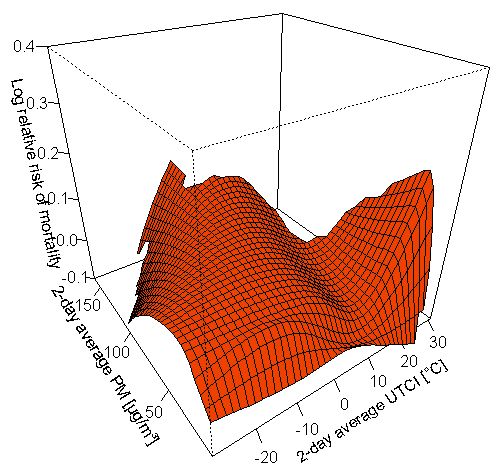

Human health is the basis of our life. The urban living and environmental conditions significantly influence the well-being, the health and the life expectation for urban populations. The environmental impacts on human health in the context of the urban climate can be derived from the bioclimatic properties of the city, especially as determined by urban heat islands and air pollutants.

Already today, but especially in the future, the specific features of the urban climate in conjunction with the impacts of climate change, the ageing of society, urban lifestyles and an unequal social distribution of environmental loads pose great challenges for the design of urban living spaces.

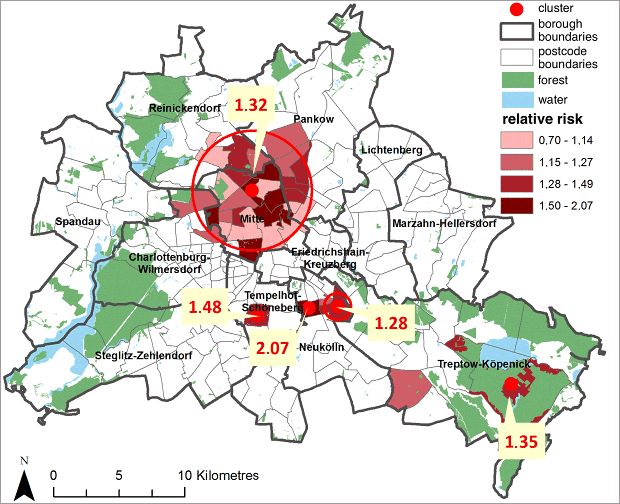

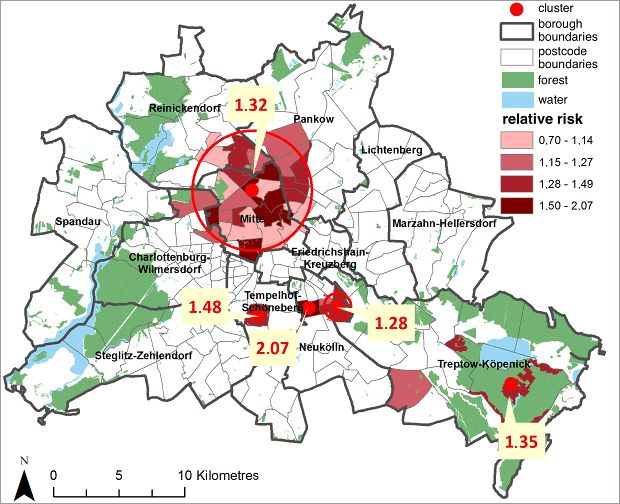

Since metropolises such as Berlin exhibit an inner-city mosaic of different urban, population and social structures as well as environmental conditions, health impacts are likewise spatially differentiated. Thus, not only the environmental conditions in an urban area are crucial, but also the proportion of the groups of persons who exhibit a particular vulnerability towards these loads. Especially elderly, chronically ill or socially deprived people and those living on their own are often affected by environmental loads to a greater extent (Böhme et al. 2013).

In order to preserve or create an urban environment healthy for humans, it is on the one hand crucial to understand the impacts of the urban climate on health. On the other hand, spatially differentiated considerations concerning human-environment relations in urban areas form an important basis. Urban planning has a significant task in this regard, particularly with respect to the impact of climate change. The Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development and the Environment published the Urban Development Plan Climate (SenStadtUm 2011) in 2011 and developed the partial climate protection concept “Adaptation to the Impacts of Climate Change” (“Anpassung an die Folgen des Klimawandels”, SenStadtUm 2016) in the framework of the climate adaptation strategy of the State of Berlin.

Planning advices maps support the aim of preserving or creating a healthy urban climate. In assessing situations of urban climate load and relief functions and in designating areas with particular urban climate deficits and vulnerability towards the urban climate, demographic structures are taken into account in addition to land use and the supply with green spaces. The identification of increased health risks through thermal load and air pollution on the basis of health-related data in spatial resolution can be understood as an important supplement for the planning and implementation of mitigation and adaptation measures for health protection.

What is the connection between urban climate and human health?

Urban structures modify the bioclimatically relevant parameters air temperature, humidity and airflows, and the exchange of radiation and energy. The urban climate can impact on humans directly and indirectly, since urban heat islands and air pollutants in the urban atmosphere not only have a direct influence on humans, but also on water, soil, flora and fauna in the city. And through these partial spheres (hydrosphere, pedosphere, biosphere), indirect effect pathways to humans can also be traced. In the following, the focus of the considerations will be on the direct impacts of the urban thermal load on human health.

Urban heat islands

The urban heat island has both a beneficial and a detrimental bioclimatic impact on human health. A shortening of the winter frost season and a reduction of the number of heating days, through which air pollutant immissions decrease (Kuttler 1998) and the risk of cold-related illnesses and deaths is reduced, is to be assessed positively. However, shortened frost seasons and milder winters also entail an extension of the vegetation period and thus the pollen season, which can increase and exacerbate allergies and change the allergen spectrum (Eis et al. 2010). Increased risks of infection are also to be expected, as the conditions for alternate animal hosts and carriers (vectors) of pathogenic organisms to live and proliferate are more favourable (Eis et al. 2010). The urban overheating has negative effects especially in the summer months, when the intensity is greatest at night. As these particularly heavy loads coincide with the nocturnal recovery phase of humans, they constitute an additional strain for the human organism on continuously hot days (Koppe et al. 2004). However, high air temperatures, low wind intensities and spatially diverse radiation conditions can lead to heat stress also during daytime in the summer. The degree of thermal load is mainly determined by the insolation.

Heat waves, i.e. several consecutive days with thermal load, are a special problem in cities, as buildings and impervious areas heat up over days, store this heat and release it with a delay. If there is no adequate night-time ventilation in these cases, residents in these urban areas experience a continuous thermal stress across the day and night hours, whereas residents in favourable urban areas experience heat relief overnight through the cooling influence of adjacent open spaces. Berlin distinguishes itself with its outstanding mixture of developed and green areas through a mosaic of different micro-scale climates and thus large differences in the thermal conditions in a small space. Assessing their climatic impact is a priority task of the three-part Planning Advices Urban Climate Map.

Thermal load

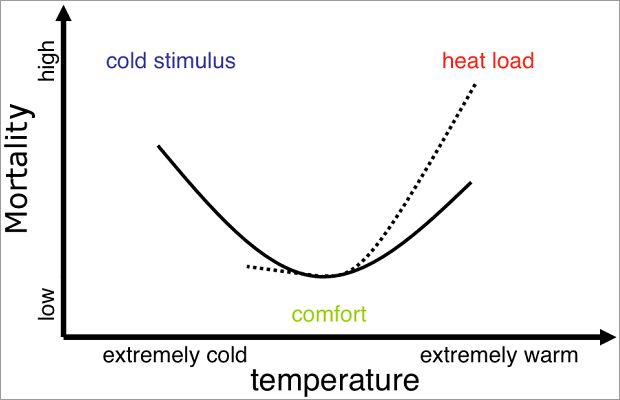

Thermal load is understood as a health-relevant assessment of the thermal environment. The thermal load is determined either by means of simple methods, e.g. threshold values of the air temperature (climatological threshold days), or by means of complex methods, e.g. via the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV), the perceived temperature, the Physiological Equivalent Temperature (PET) or the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI), an update of the Klima-Michel model applied by the German Meteorological Service and of the perceived temperature (Koppe 2005, Jendritzky et al. 2009). The thermal load is divided into heat load and cold stimulus. A severe thermal load is also referred to as a heat load or heat stress, but the terms are often used synonymously and there are no standardised definitions.

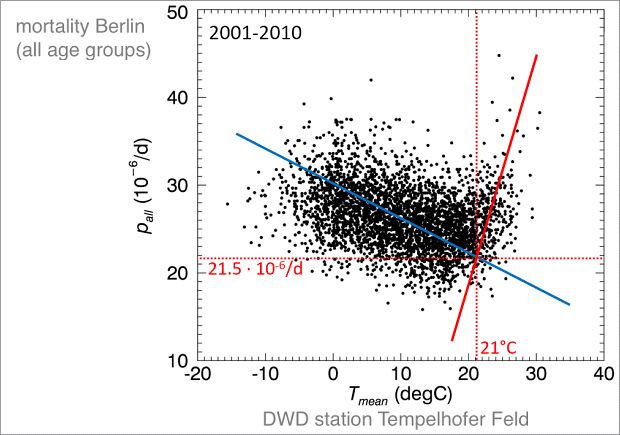

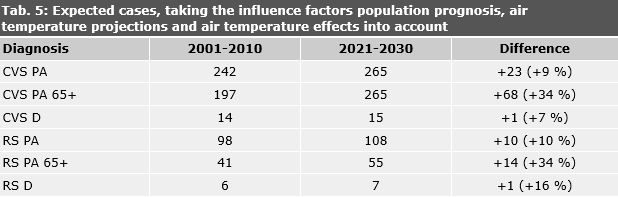

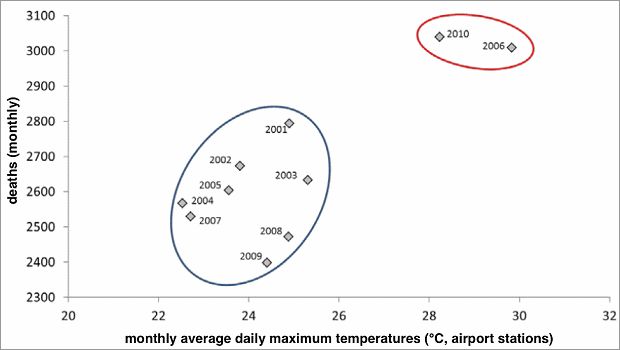

If the mortality (mortality or mortality rate related to the total population) and e.g. the air temperatures are considered across the calendar year, one usually finds a U-shaped curve (cf. Figure 21).