Breeding birds are for various reasons well-suited as indicators for the evaluation of habitats. They occur in almost all landscape types and settle them quickly, they display no extreme fluctuation of population, and, since they are at the end of the food chain, they make complex demands upon their respective habitats.

They are generally well-studied, since there are so many interested avifaunistic (ornithological) persons and groups; moreover, breeding birds are relatively easy to observe.

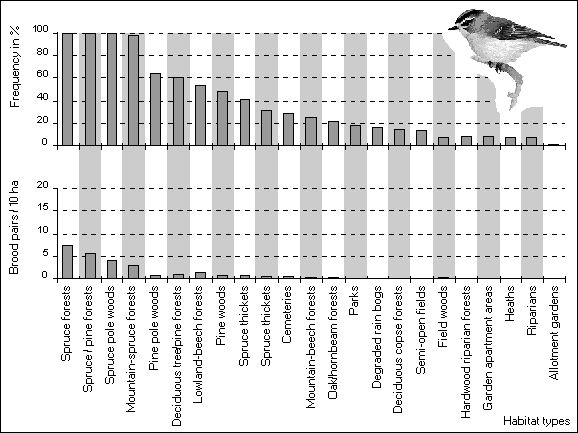

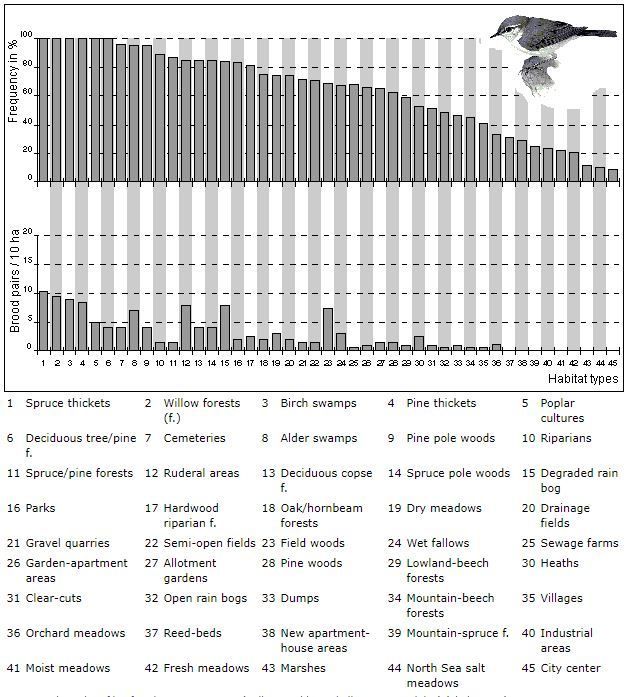

Indicators react in visible ways to ecological damage, and thus represent other groups of organisms, or whole biotic communities. Breeding birds can, as indicators, indicate deficits and qualities of habitats, such as near-naturalness, structural diversity, intensity of disturbance or the relationship to other habitats, (cf. Matthäus 1992) and thus form a basis for conservation planning. This is especially true of indicator species (Leitarten) in the present sense, i.e., those specialized toward particular habitats. According to investigations by Flade (1991, 1994) indicator species reach significantly higher frequency (abundance or sighting probability in the investigation areas, which are usually at least 10 ha in size), and usually also markedly higher settlement density (brood pairs per 10-ha investigation area) in only one, or in a very few, habitat types, than in all other habitat types. In their preferred landscape types, indicator species find their required habitat structures significantly more often and, most importantly, more regularly, than in all other landscape types. Ubiquitous species (garden-variety species) are of little significance by comparison, because of their slight degree of specialization. The goldcrest, as an example of an indicator species, shows high frequency and settlement density in only four habitats characterized by spruce (cf. Fig. 1). For the willow warbler, by contrast, as an example of a ubiquitous species, significantly preferred habitat types cannot be ascertained (cf. Fig. 2).