The graphical representation of the assessed structural heating data for Berlin’s residential and commercial spaces provides a useful tool for analyzing both larger-scale contiguous areas and self-contained sites.

Map 08.01 Building Heating Supply Areas

Fuel consumption in buildings greatly depends on their structural layout and geographical location. Marked differences can be noted between the city’s 12 boroughs; usage of the different energy carriers varies greatly depending on the boroughs’ respective locations within the city (cf. fig. 2).

Map 08.01.1 District Heating Supply Areas reflects very clearly the local proximity of heating plants and heating power plants to their respective supply areas. The largest share of district heating in Berlin is provided by BEWAG, with a network spanning approx. 1,200 km. The great majority of the 7,260 blocks with access to a district heating network also make use of this heating option (more than 60 percent). In newly developed and existing outskirt residential areas such as Hohenschönhausen, Marzahn or Märkisches Viertel, many large housing estates are supplied exclusively with district heat. Altogether, the map demonstrates Berlin’s leading position in Europe for the supply of district heating. Since 1995, many of the potential candidates for district heat connection – particularly coal-heated old buildings bordering existing district-heat-supplied areas – have been integrated into the networks.

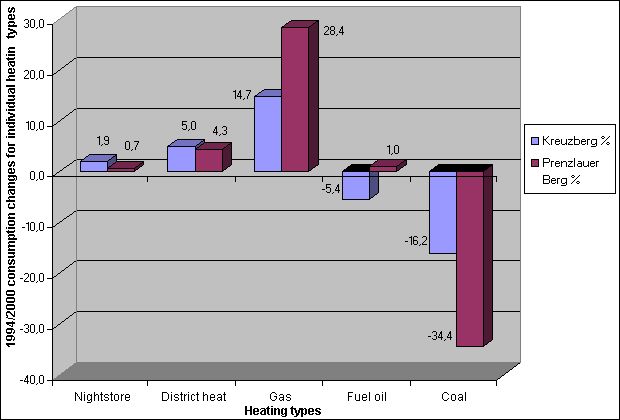

Map 08.01.2 Gas Heating Supply Areas shows the finely meshed distribution of the gas pipe network over the entire Berlin conurbation. In contrast to the 1994 survey, the proportional shares of gas heating within the respective statistical blocks are no longer just between 10 and 40 percent. As well as in the areas that were already committed to gas heating in 1994, gas has also become the primary heating energy carrier in large areas of Kreuzberg, Neukölln, Friedrichshain, Prenzlauer Berg (cf. fig. 8), southern Pankow, and to a lesser degree Köpenick and Treptow. Isolated administration, service provision and production sites all over Berlin are also taking advantage of the gas network. As is the case with district heat, most of the new gas connections have been introduced in blocks that previously relied on coal for their heat supply.

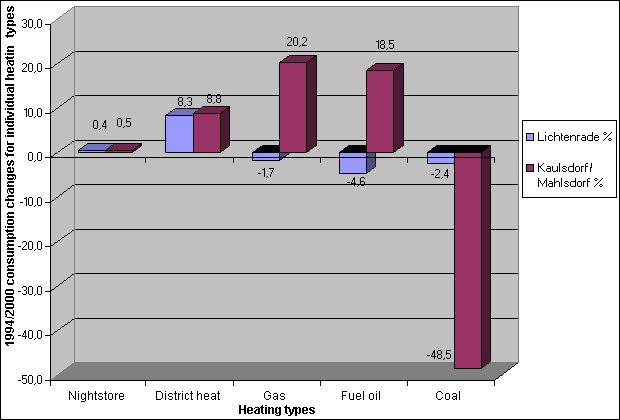

Before the unification of the two city halves but also as late as 1994, there was only very little oil-fired building heating to be found in the eastern part of Berlin, and in virtually no block was fuel oil the predominant energy carrier. Map 08.01.3 Oil Heating Supply Areas (supply situation 1999/2000), however, indicates that today there are numerous blocks that use fuel oil for more than 80 percent of their heating requirements, particularly in those areas of eastern Berlin that do not have access to the pipe networks. The geographical spread shows no clearly defined centers, instead there is a narrow stretch of fuel oil usage along the eastern city perimeter. The increase in oil heating that was to be expected after 1994 can largely be traced to the organized replacement of coal-fired hot-water boilers (cf. fig. 7).

In the eastern part of the inner city, on the other hand, there are virtually no blocks that rely on fuel oil for heating.

Supply structures in the western part of the city have undergone much less change. In the suburban housing areas on the city outskirts, fuel oil continues to dominate as the primary heating source. The fuel oil share of the total heated floor area in such blocks is often well above 60 percent.

Major shifts towards pipe-dependent heating systems are to be found in a number of inner city areas, for example, south of Bismarckstrasse in Charlottenburg.