Original situation

Ground-level emissions from motor vehicle traffic is the most influential factor in the assessment of traffic-related air pollution. Causes and effects are therefore presented in two maps that are closely related:

- Traffic-Related Emissions (Environmental Atlas 03.11.1) and

- Traffic-Related Air Pollution (Environmental Atlas 03.11.2).

The original situation is identical in both maps, a description of which may be found in the relevant section of Map 03.11.2.

Effects

Nitrogen oxides are acidifiers. They are harmful to human health, cause damage to plants, buildings, and monuments, and contribute significantly to the excessive formation of ground-level ozone and various noxious oxidants during summer heat waves.

Nitrogen oxides, especially nitrogen dioxide, lead to irritation of the mucus membranes of the respiratory passages in people and animals, and can increase the risk of infection (cf. Kühling 1986). Cell mutations have also been observed (BMUNR 1987). Various epidemiological studies have shown a correlation between the deterioration of the functions of the lungs, respiratory tract symptoms, and increased nitrogen dioxide levels (see Nowak et al. 1994).

Diesel soot is a major component of particulate matter (PM10) in motor vehicle exhaust. It is a carrier for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), a carcinogen, but also on its own, it is a possible cause of lung and bladder cancer (see Kalker 1993). Moreover, such ultra-fine particulate as diesel soot, smaller than 0.1 µm, is suspected to increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Legal stipulations and limit values

An evaluation of air pollution from motor vehicle traffic has only become concretely possible for immission control authorities since 1985, since the European Community, in the Directive of the Council of 7 March 1985 on Air Quality Standards for Nitrogen Dioxide (Directive 85/203/EEC), specified limits and goals for this pollutant. In addition, it stipulated that measurements be taken of concentrations of nitrogen dioxide on “urban canyons” and major intersections.

In 1996, due to a multiplicity of new findings regarding this and other air pollutants, “Directive 96/62/EC on Ambient Air Quality Assessment and Management (the so-called “Framework Directive”) was drafted and brought into force.

In this Directive, the Commission is called upon to submit, within a specified time period, so-called “subsidiary directives” stipulating limits and details for the measurement and assessment of a specified list of components.

Since then, four subsidiary directives have come into force:

- as of July 19, 1999, Directive 99/30/EV, with limits for sulphur dioxide, particulate matter (PM10), nitrogen dioxide and lead

- as of December 13, 2000, Directive 2000/69/EC, with limits for benzene and carbon monoxide

- as of February 9, 2002, Directive 2002/3/EC, for comparing ozone at ground level to the data and level of excess over the limits; and

- as of December 15, 2004, Directive 2004/107/EC, with limits for arsenic, cadmium, mercury, nickel and PAH.

Germany had two years to enact the first two subsidiary directives into national law, a deadline it missed substantially, as the Seventh Amendment to the Federal Immissions Protection Law (BImSchG), which addressed the first subsidiary directive, was not enacted until September 2002. The new Ozone Directive has now also been enacted into German law with the new 33rd Ordinance of the BImSchG.

The core elements of the Air Quality Directives are the immission limit values, which are “to be attained within a given period and not to be exceeded once attained”. The pollution concentrations, and the time in which the limits must be met, are stipulated in the subsidiary directives, and in the 22nd Ordinance of the BImSchG (22nd BlmSchV).

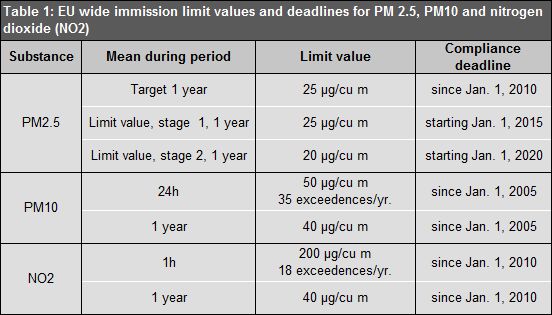

Table 1 shows the corresponding values for the air pollutants which pose the greatest potential problem for Berlin: PM2.5, PM10 and nitrogen dioxide.