Areas with a special vulnerability as compared to the urban climate

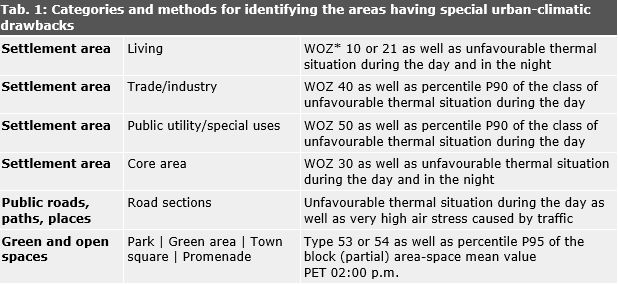

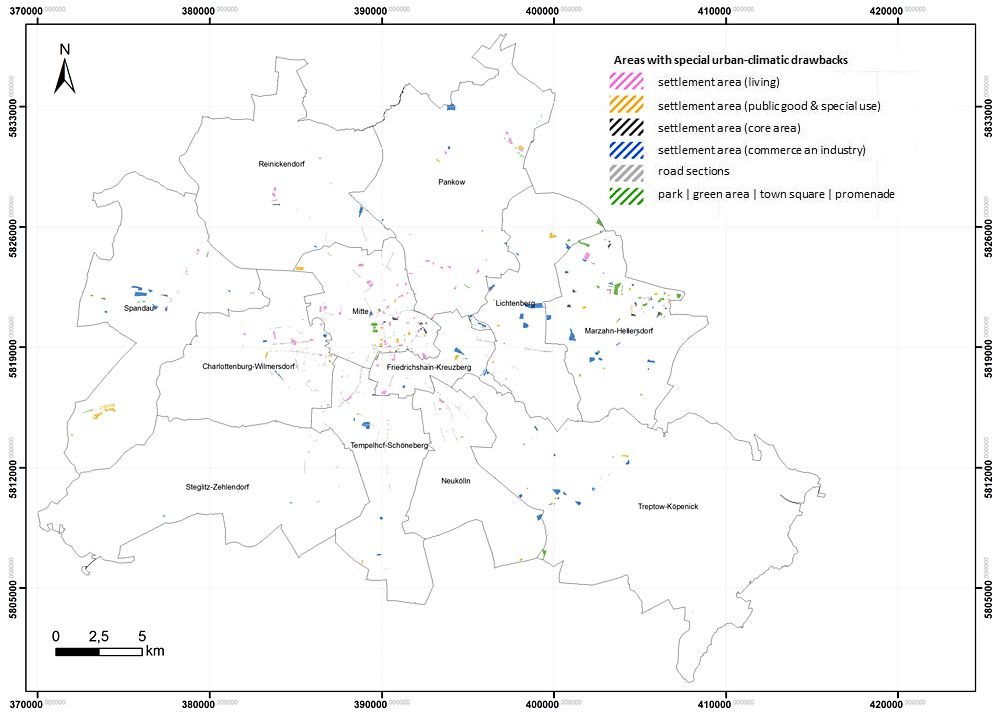

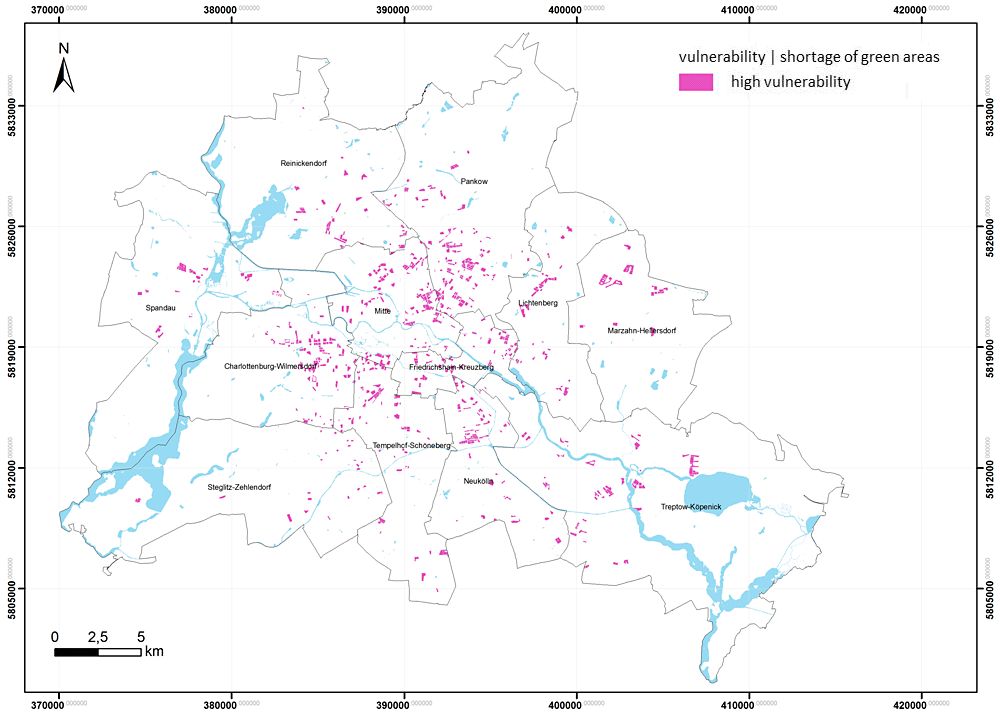

The identification of areas with a special urban-climatic drawback is based on a purely planning, climatic perspective. Their connection with further non-climatic criteria can disclose additional decision-making helps in the context of implementation of measures especially for the spatial unit “settlement area” as defined in a spatially differentiated vulnerability study.

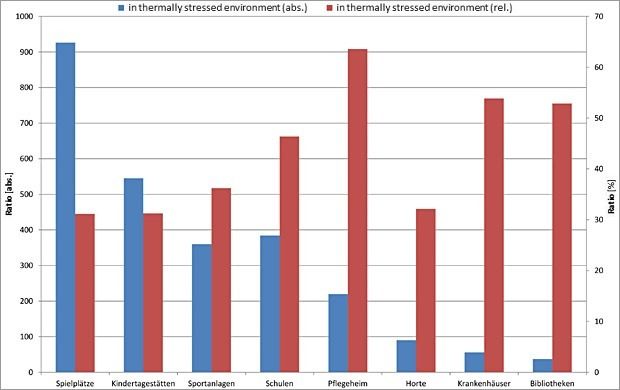

To what extent the block areas of the settlement area are vulnerable to the city-climatic situation depends on primary criteria of time of stay/use as well as on further secondary factors. These include, above all, the demographic composition of the quarters observed. Apart from this, the availability of specific sensitive building/area uses as well as the degree of supply of residential areas with adequate green areas are the factors that influence the level of vulnerability.

h5. Special vulnerability based on demographic composition

Especially sensitive to the thermal (heat) stress are mainly the older people in the population (above 65 years [Ü65]) owing to the susceptibility to cardiovascular disorders increasing with age as well as small children below 6 years (U6), and mainly infants because of their lacking or not fully developed ability for thermal regulation (Jendritzky 2007). A relationship between an increased mortality and the occurrence of heat periods can be shown empirically for the areas of Berlin-Brandenburg and can also be mapped in a model (Scherber 2014, Scherer et al. 2013, Fenner et al. 2015).

In-depth information about the relationships between “Health and urban climate” is offered by the related excursus (Scherber 2016).

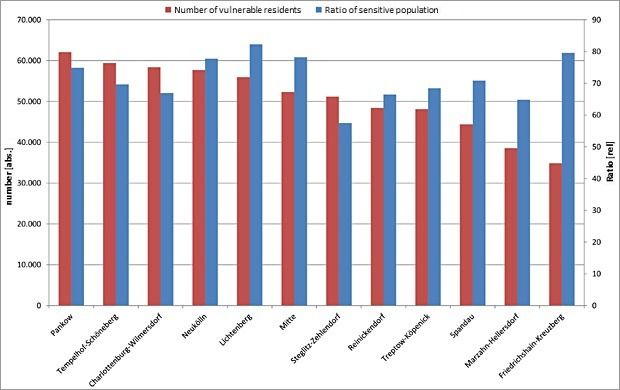

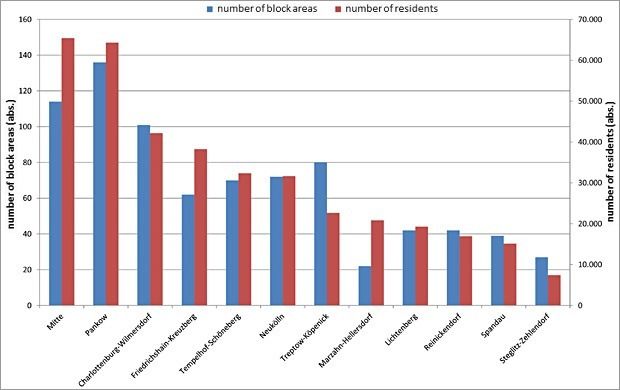

About 850,000 people live in Berlin, for whom a special thermal sensitivity can be assumed owing to their age (Statistics BBB 2014). The ratio of the sensitive older and the sensitive younger percentage of the population is approx. 3.4:1. It applies equally to all districts that the risk group of older people is much higher than that of small children and infants. This phenomenon is most strongly pronounced in the district Steglitz-Zehlendorf (5.3:1), where just about 90,000 of the thermally most sensitive residents of Berlin live. In Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg – the district with the lowest number of thermally sensitive residents (approx. 45,000) – there are only 1.6 Ü65 year old for one person in the age of U6.

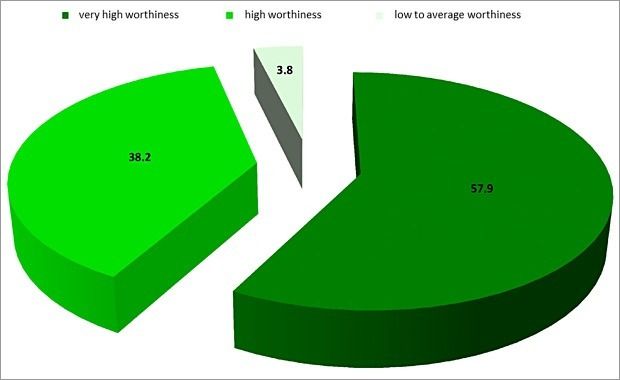

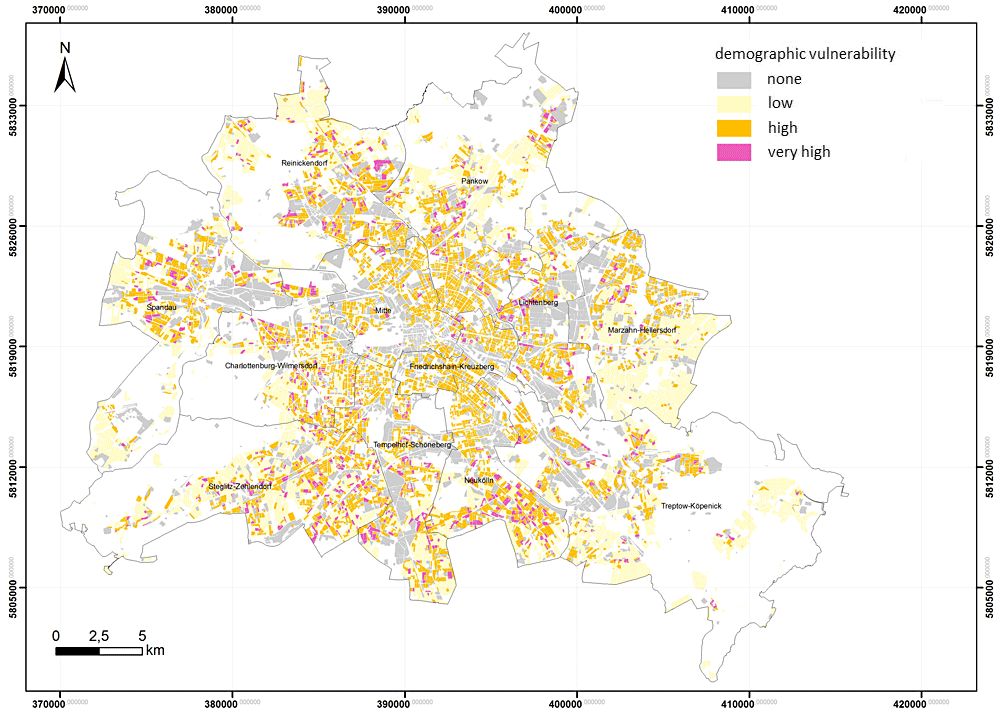

To what extent can an actual vulnerability also be derived from this sensitivity, depends essentially on the geographic distribution of the risk groups in the spatially differentiated stress field. In the result, there is a high or very high demographic vulnerability in approx. one third of all block areas, Approx. three quarters of all heat-sensitive Berliners live in these areas (around 650,000 residents). Vice versa, it also means that measures need to be implemented only in a comparatively small area, in order to give thermal relief to a high percentage of vulnerable population group.

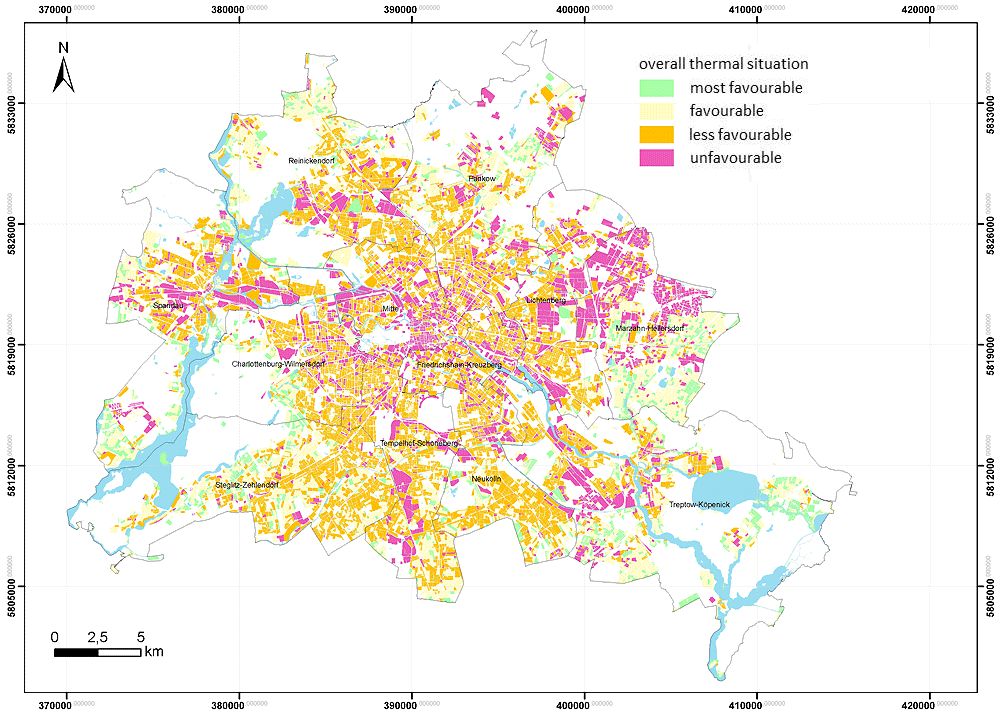

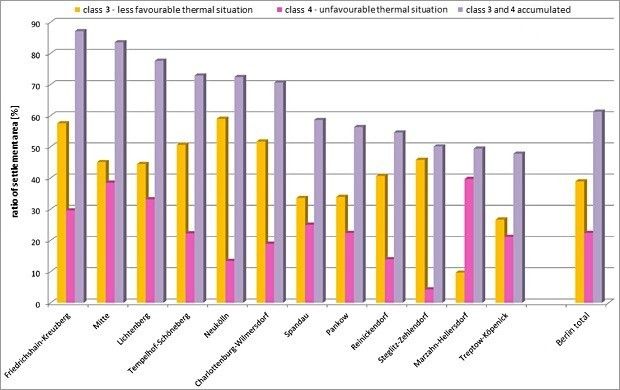

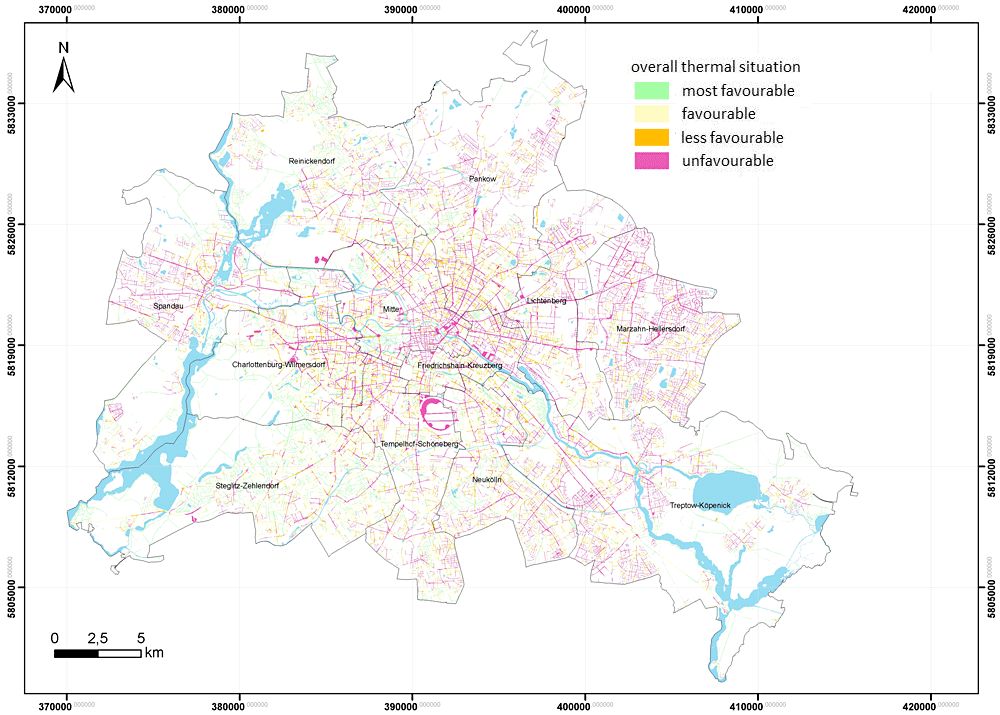

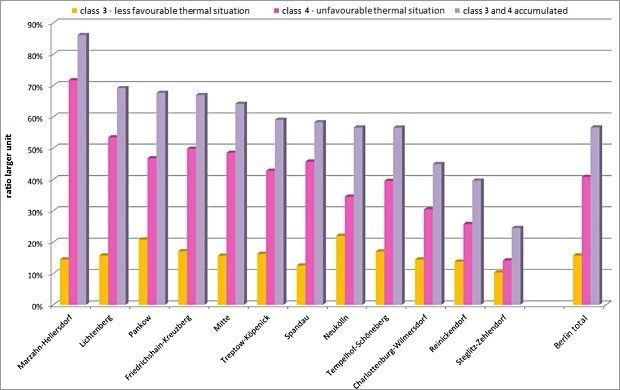

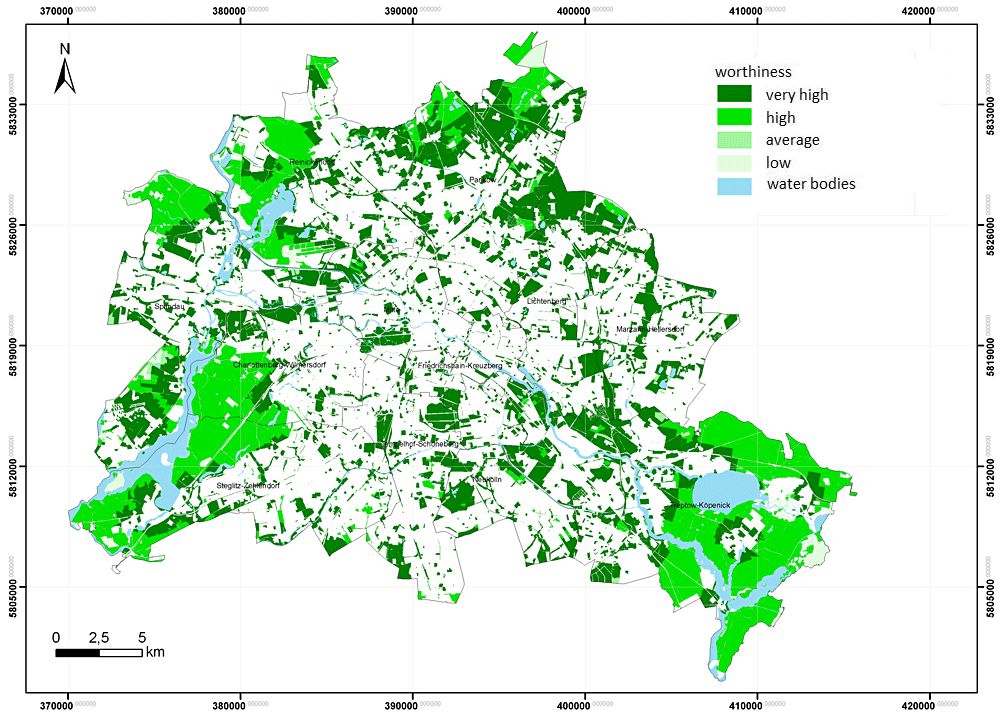

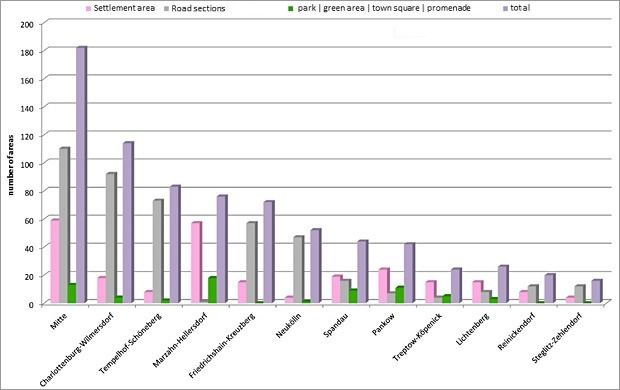

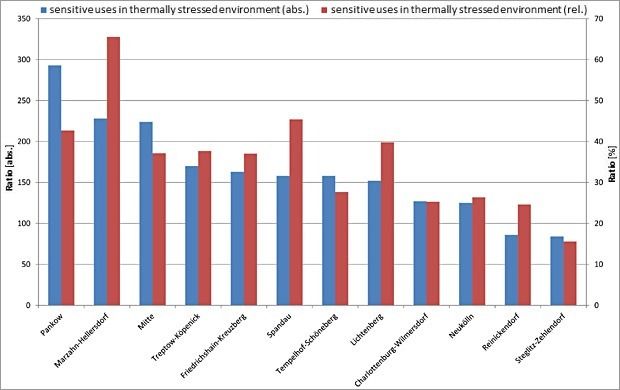

A spatially differentiated analysis at the level of Berlin’s districts shows that although there is a fundamental agreement in the distribution of population groups sensitive to climate with the space patterns of the actual demographic vulnerability, but there are still some essential differences (Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Thus, although the district Steglitz-Zehlendorf is the biggest group of thermally sensitive persons, the district has only rank 7 in case of demographic vulnerability. The reason for this is firstly that the stress level lies on the whole below the average. Secondly, the risk groups are currently living in thermally favourable areas. The reverse case applies to Pankow. Seen absolutely, there is the highest demographic vulnerability here, although the district has only the fourth largest sensitive population.

At the lower end of the scale, both the results match in contrast: Spandau, Marzahn-Hellersdorf and Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg show the lowest number of sensitive persons as well as the demographic vulnerability. However, it applies to Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg that the majority of the sensitive population also lives in areas with thermal stress (approx. 80 %). A higher percentage is also seen in the district of Lichtenberg (82 %). Even Mitte and Neukölln lie at the same level.