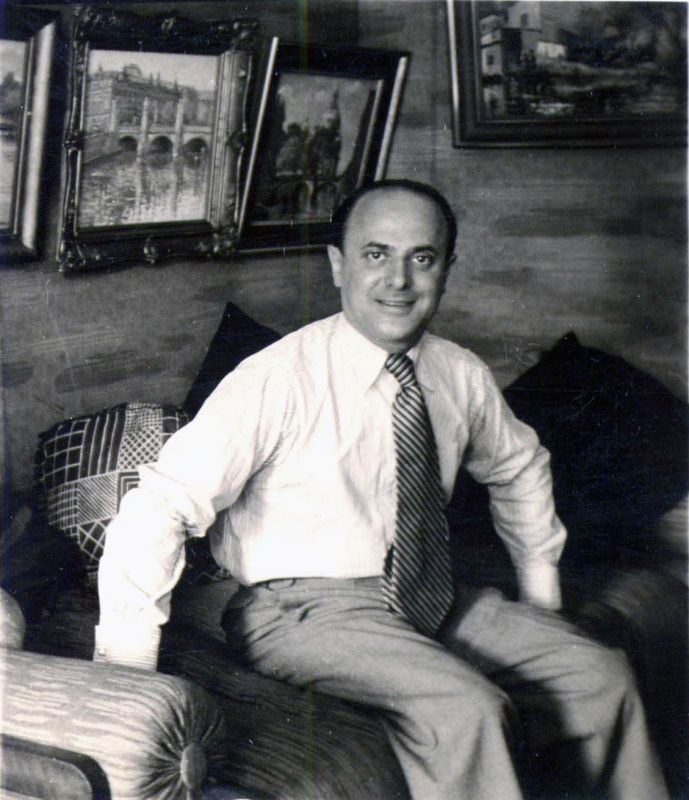

GOA first moved the family to Chicago and then to St. Louis. After only fifteen months in America, Friedmann had been appointed to the position of top artist at this branch. Instead of pictures from the concentration camps, he painted two-story tall billboards with iconic Clydesdales and happy folks selling beer. The new career brought recognition and satisfaction with life in America. In 1960, the Friedmann family became proud United States citizens and symbolically dropped the double “n” spelling of the surname.

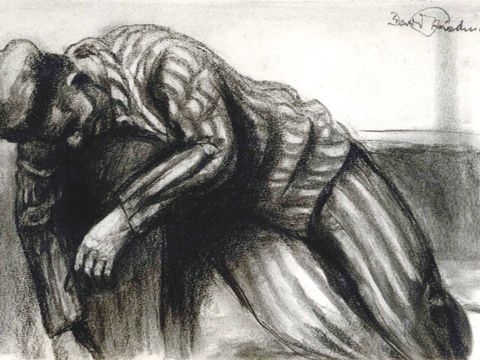

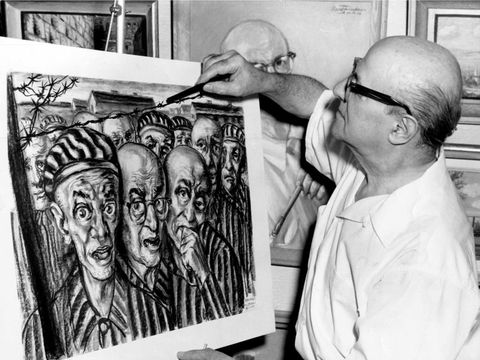

After retirement in 1962, his art would not be silent. He produced a second series of Holocaust art to fight antisemitism and race hatred of all people. The David Friedman Exhibition opened first in St. Louis in 1964, followed by Baltimore, Maryland in 1965, marking the 20-years anniversary of liberation, and was even reported on in the Israeli press.

Friedmann died at the age of eighty-six on February 27, 1980. He is recognized internationally with works on permanent display at the Holocaust History Museum, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem; the St. Louis Holocaust Museum & Learning Center; and the Sokolov Museum in Czechia. His works are in the collections of numerous institutions and museums, such as the Leo Baeck Institute, New York and Germany; the New Synagogue Berlin-Centrum Judaicum; the State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau, Poland; and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DC. Exhibition venues include the Berlin Philharmonic Hall in Germany, the Terezín Memorial in Czechia, the United Nations Headquarters and the German Consulate General in New York.

In 1954, Friedmann was among the first to win restitution from Germany for Nazi-looted art. The sum incorporated claims for all his looted property. He continued to fight for justice. In 1961, the International Supreme Restitution Court in Berlin adjudicated an upward adjustment.

David Friedmann was a successful artist with both Jewish and non-Jewish clientele. Art was sold privately, at galleries, exhibitions and auctions. Fleeing the Third Reich, most emigrants found it necessary to sell their art to finance an escape. Others managed to flee with their art.

Artwork often continues to find new owners — sold at auction or through private sales — purchased by people who are not known as collectors. Pieces are displayed on walls of family homes for generations, art they enjoyed all these years, not knowing the paintings have a history and the artist’s daughter is searching to find them. David Friedmann artwork has surfaced all over the world — the Netherlands, Denmark, Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Italy, Czechia, Poland, Israel, Australia, China, Canada and the United States. I have just started to find his pre-war art over the last two decades.

Every painting to emerge is a victory against the Third Reich. David Friedmann made important contributions both in the realms of 20th century art and in the creation of materials that play a powerful humanitarian role in educating people about the reality of the Holocaust.

My goal is to publish a catalogue of his works, evidence of the brilliant career the Nazis could not destroy.

For more about David Friedmann and to provide information you may have about existing works, please visit: www.davidfriedmann.org or the “David Friedmann – Artist as Witness” Facebook page.

With thanks to the National Library of Israel, who originally published this article in its blog. https://blog.nli.org.il/en/lbh_friedmann

Miriam Friedman Morris, USA

Leichte Sprache

Leichte Sprache DGS

DGS